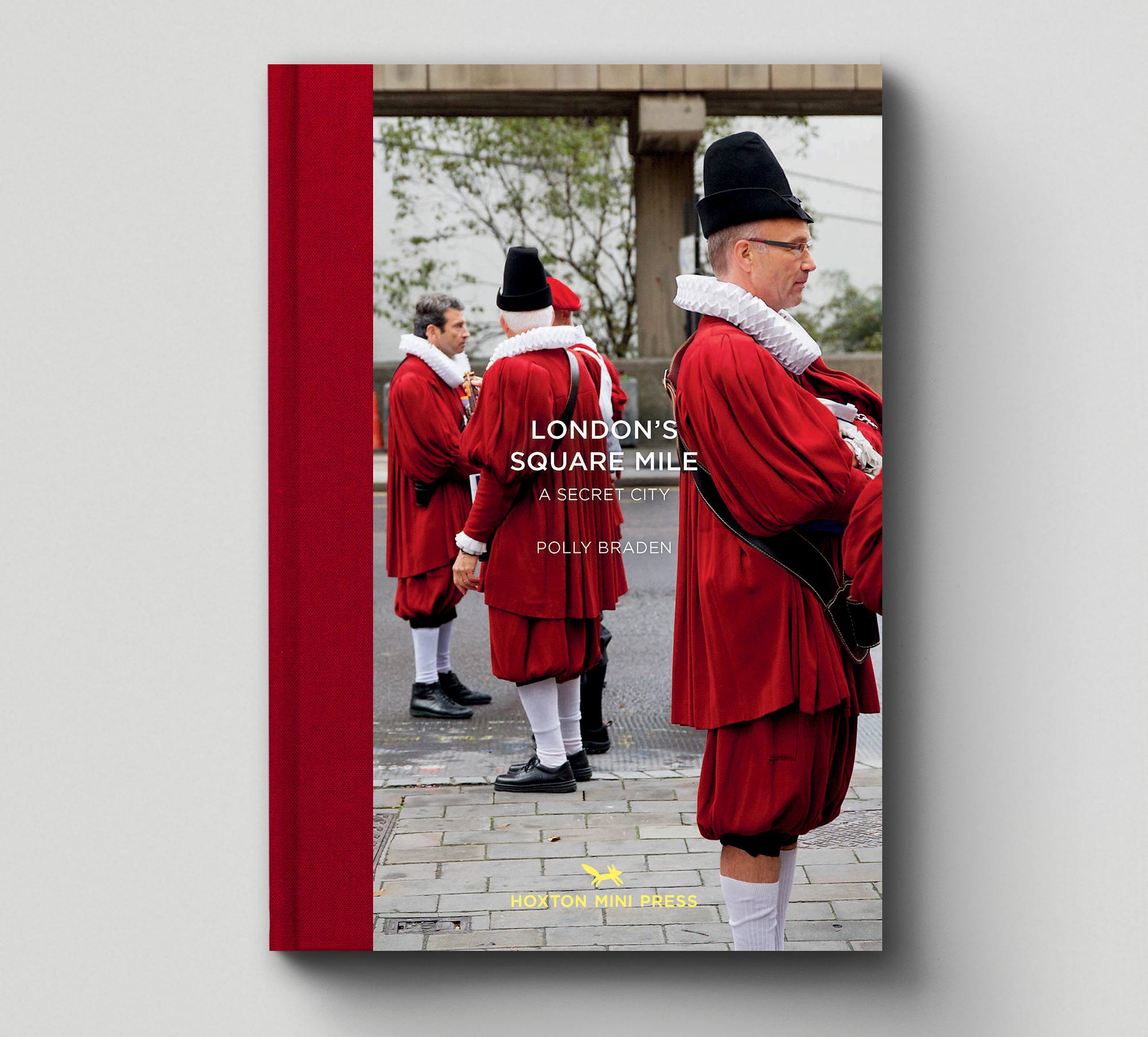

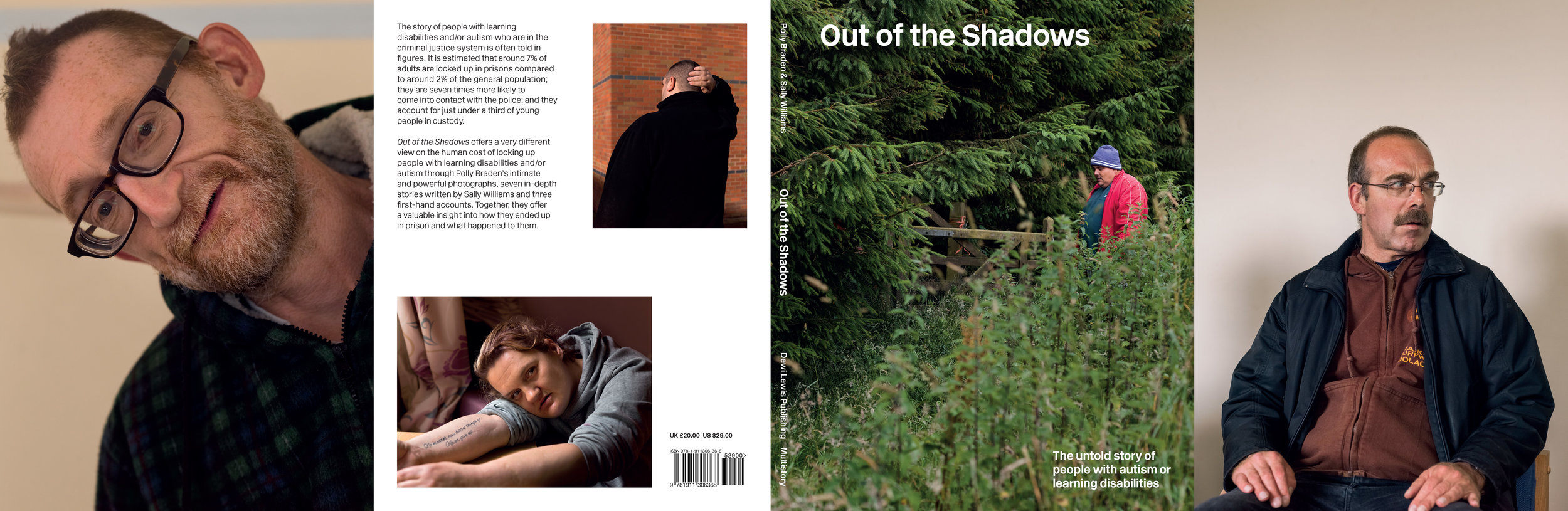

Published by Hoxton Mini Press

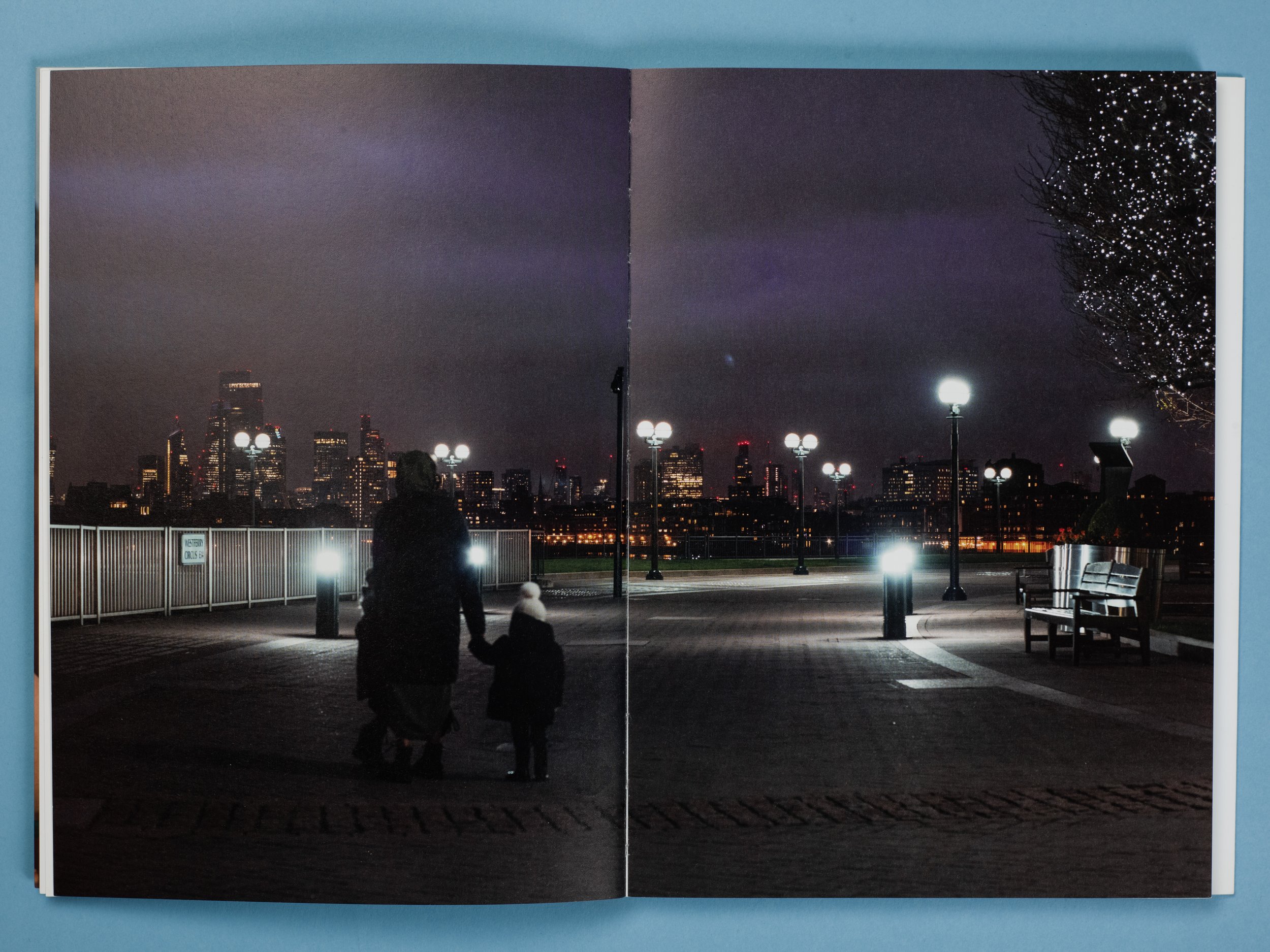

Millions pass through the square mile, also known as the City of London, yet few are aware of its true significance. These photographs of people surrounded by the City’s imposing architecture, combined with texts from an acclaimed historian, David Kynaston, begin to decode one of the most cryptic and fascinating parts of the capital.

An extract from David Kynaston’s introduction:

“I have seen the West End, the parks, the fine squares, but I love the city far better,” reflects Lucy Snowe, the heroine of Charlotte Brontë’s 1853 novel Villette. “The city seems so much more in earnest: its business, its rush, its roar, are such serious things, sights and sounds. The city is getting its living – the West End but enjoying its pleasure. At the West End you may be amused, but in the city you are deeply excited.” By ‘the city’, she meant of course the City of London.

The City has always been a world of its own: not only in the obvious sense of its distinctiveness, its apartness from the rest of London, but also because of the extent and might of its global reach, affecting distant peoples about whose daily lives and circumstances the City’s movers and shakers know little or nothing. Nor for their part do most outsiders – even in the rest of London, let alone further afield – have a more than nugatory grasp of what kind of place the City is, or how as the world’s leading international financial centre it has got to where it is now. So, briefly, some history.

Starting with the Romans, who established at the lowest bridging point of the Thames that area we know as the City, essentially as a trading centre with northern Europe. By the end of the reign of Elizabeth I, as trade flourished with almost all parts of the known world, it had become the largest port in the world. Then, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the City became an ever more prosperous commercial centre on the back of naval power and the start of the British Empire, while at the same time recognisably modern financial institutions began to emerge: Lloyd’s maritime insurance market (under way from 1691); the Bank of England (1694); and an organised stock market (originally in coffee houses, but from the 1770s in more permanent premises).

The City’s zenith came during the largely peaceful century between the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. This was sterling’s heyday, as in an era of unimpeded capital flows the City willingly – and lucratively – serviced the needs of a rapidly expanding global economy. It did so in all sorts of ways, whether through its role as the world’s great capital market, or through providing trade finance (‘accepting’ bills of exchange), or through a whole range of other commercial services (organised via such institutions as the Baltic Exchange or the Wool Exchange or the London Produce Clearing House). ‘All Lombard Street to a China orange’ was a popular Victorian phrase, referring to the high probability of something happening. It was also eloquently revealing: Lombard Street (home to the discount houses which operated London’s all-powerful money market) as the very epicentre of the global machine; China as a remote, peripheral player. Put another way, the City during these years was the greatest international financial and commercial centre that the world had ever seen – and would, in all likelihood, ever see.

Then came the guns of August 1914. Over the next half-century, featuring two world wars (including physical devastation of the square mile during the second), New York largely supplanted London as the dominant centre. The City stagnated, and became, in short, a club, with an accompanying club-like mentality: conservative, complacent, exclusive. ‘Cars are black’ was one of a trio of celebrated maxims of a prominent post-war stockbroker, Cedric Barnett. ‘Shoes have laces.’ And of course: ‘Jelly is not officer food’. Yet the other side of the club coin was that it was a place where trust mattered, where most business was conducted on a face-to-face basis, and where the Stock Exchange’s traditional motto, ‘My word is my bond’, actually meant something. Most of the City’s critics rightly identified the lack of dynamism and meritocracy; not enough appreciated the preciousness of trust and the importance of the personal.

That said, the so-called ‘Big Bang’ of 1986 was arguably decades overdue. Back in the 1960s the City’s somewhat fortuitous success in becoming the main location for the Euromarkets had pointed the way to a City returning to its pre-1914 internationalist roots; but it was not until the 1980s that the Stock Exchange was opened up to foreign players – and then only as a result of fierce external pressure from Margaret Thatcher’s government. Almost at a stroke, and abetted by fast-moving technology, the City changed fundamentally: serious competition; serious money; and general Americanisation. Or as one survivor from the old days ruefully informed the well-named magazine Futures World, ‘I arrive before the tea lady now’.

It is now more than a quarter of a century since the City revolution (as it was often called). The main outlines of the subsequent story are clear enough: the almost complete failure of the long-established British merchant banks, traditionally the City’s crème de la crème, to thrive in the new, harsher world; the importation of the pernicious American dogma of shareholder value, encouraging high-street banks to concentrate less on financial stability, more on a high share price (with accompanying high bonus pay-outs); the greed and hubris that preceded the 2008 crash; the still-being-played-out consequences of that crash; and the potential threat of Brexit to the City’s international business. Most historians and commentators would accept that the City needed its revolution; but it did not need to be this way.

Any critique – any attempt to reform the City – has to end as well as begin with the human dimension and an understanding of the environment in which those humans operate. Polly Braden’s atmospheric, intensely evocative photographs remind us that the square mile is still just as much a world of its own as it was in Charlotte Brontë’s long-ago days. Yes, the modern City has become a self-perpetuating, over-rewarded island, too much cut off from the rest of Britain. But it would be a shame, even a tragedy, if it were ever to lose completely its own very particular specialness.

Exhibited at Fotofestival Mannheim, Heidelberg, 2015, DE

Buy the book